Cotton and the Closed-Loop Economy

Key Takeaways:

Cotton, depending on how it is grown, can either destroy its surrounding landscapes and habitats, or serve its purpose with minimal environmental impact, while supporting the livelihoods of farmers.

The duality of the benefits of cotton versus the damage it could cause (when it isn’t sustainably produced), makes it one of the most fiercely debated fibers in the sustainable fashion community.

It is a challenging feat to bring cotton production in line with even minimally acceptable environmental standards.

Cotton accounts for roughly 25% of global fiber production, just after polyester in terms of market share. The earliest known archaeological discoveries of cotton are estimated to date back 6,500 to 8000 years.

The natural properties of cotton has made it a must-have in our closets – it’s breathable, soft, absorbent, hypoallergenic, and more – so what’s not to love about it?

While the benefits and abundance of cotton does appeal to both manufacturers and consumers alike, there is a misconception that all natural fibers are sustainable. There is still much demystifying to do to clarify the environmental and social impact of cotton.

Impacts of the Resource-Hungry Crop

With ever rising demands for sustainably made products, cotton is increasingly becoming the target of criticism for its environmental impact.

Cotton production requires vast amounts of water to grow. Each cotton plant needs about 10 gallons of water to maximize its yield, and around 10,000 to 20,000 liters of water are needed to produce only 1kg of cotton, and that’s not even inclusive of water used for dyeing them. Ironically, underdeveloped countries with water stress are increasingly farming cotton, primarily due to low labor costs and vast farmland.

To make matters worse, pesticides are also often used in cotton production, more so than any other crop. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 84 million pounds of pesticides were applied to the country’s 14.4 million acres of cotton in the year 2000. Exposure to large amounts of pesticides could potentially cause cancer, endocrine disruption, neurotoxicity, birth defects, amongst other health concerns in a wide range of species.

This results in an increasing scarcity of clean drinking water and farmland to cultivate food crops. For instance, the amount of water used to grow cotton in India in 2013 could have supplied 85% of its population with 100 liters of water everyday for a year.

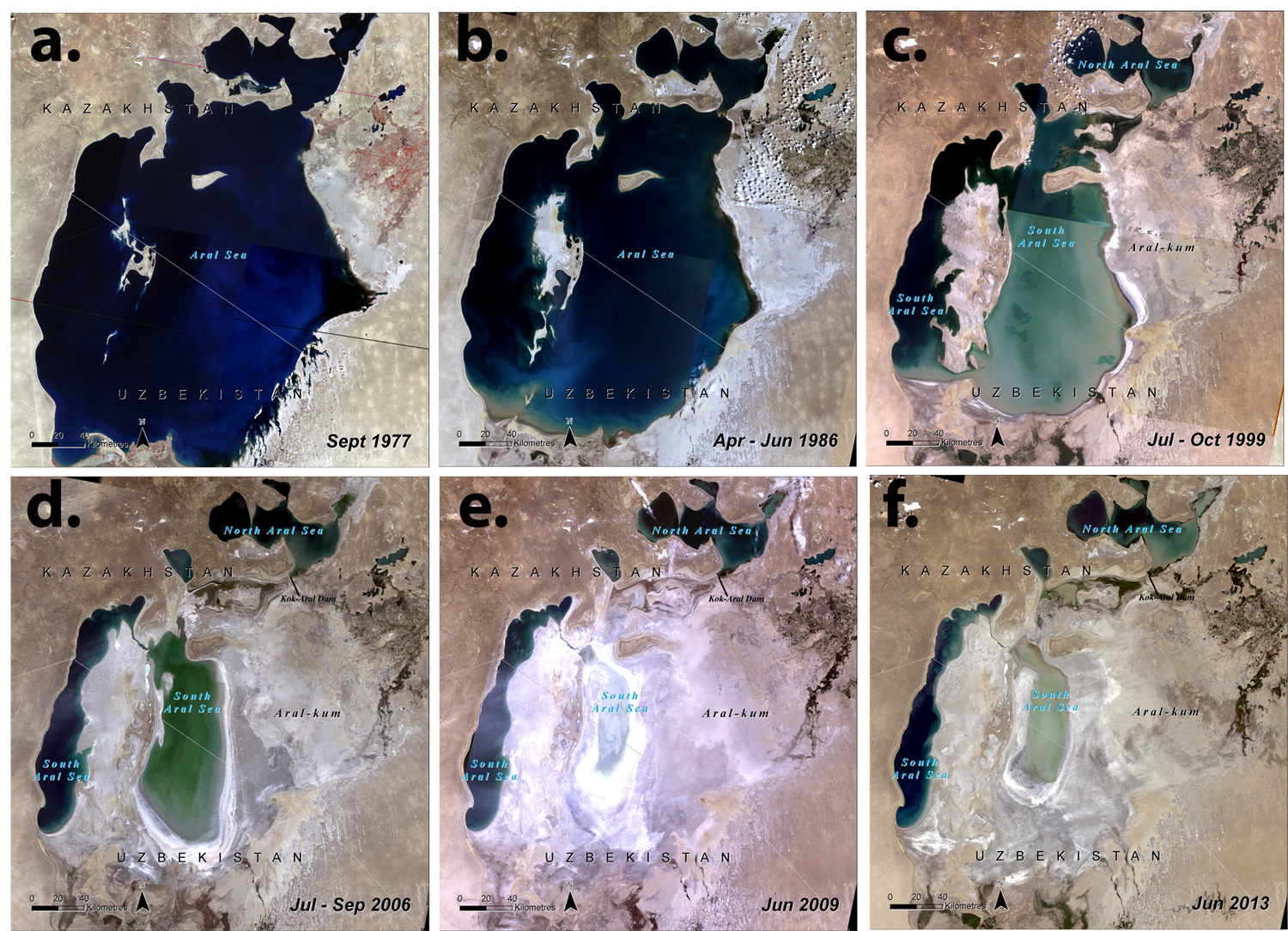

The near-disappearance of the Aral Sea — once the fourth largest sea in the world — is perhaps the most jarring example of the exploitation of the fashion industry. The intense cotton production in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan drew waters from the Aral Sea through its two main rivers, the Syr Darya and Amu Darya, drying up the sea over the years. The drastic vanishing of the sea over the past 40 years has been dubbed as ‘probably the biggest ecological catastrophe of our time‘ by the UN Secretary-General António Guterres.

The Cotton Dilemma

Research into recycling technologies have been heavily funded by prominent fashion brands and venture capitalists. But many people are unaware that the recycling of cotton in a circular economy isn’t as straightforward as it seems. To understand this we have to delve into what transpires when cotton is recycled.

First things first, there are primarily two methods in which cotton can be recycled: mechanically or chemically.

Mechanical Recycling

Cotton and wool textiles have been mechanically recycled for a very long time, way before the circular economy became the talk of the town. Used clothing is shredded during mechanical recycling to create new yarn. The issue with this is that the cotton fibers are damaged during the shredding procedure and will become shorter with each iteration. The quality of the cotton fibers will eventually deteriorate to the point where they are no longer usable, and only 30% of the recycled fibers can be incorporated into new fabrics. Quality and performance will slowly decrease with every iteration, meaning that recycled cotton only has a finite place within a circular economy.

The end product can be improved by using a blend of shorter and longer cotton fibers, or introducing virgin cotton or other fabrics into the mix to strengthen the fabric.

Chemical Recycling

Chemical recycling comes into the picture when the results of mechanically recycled cotton fall short.

Chemical recycling uses a series of chemical processes to recycle a material back into its chemical building blocks, called monomers. The resulting monomers can be used to create new chemicals and materials. Textiles which are chemically recycled are of the same quality as virgin textiles, which means that performance and quality is preserved during the recycling process, gaining chemical recycling a firm foothold in the closed-loop economy.

However, what makes cotton particularly complicated to break down is because of its cellulose structure (formed by chains of glucose monomers), which is high in crystallinity and polymerization; such traits are linked to higher fiber strengths.

When cotton is being recycled, the cellulose is first dissolved in a solvent to produce a thick, sticky solution that is then forced under high pressure through tiny holes to create new fibers.

All of the technologies for chemical processing available today use cellulose as in input, but the output is invariably rayon. Rayon are man-made fibers from regenerated cellulose. Viscose is probably the most well-known example of rayon, which may not feel like an organic fiber at first glance, but is actually one. Lyocell, or more often known as Tencel, is also another popular rayon, and has been introduced in apparels of prominent fashion labels such as H&M, Allbirds, Espirit, and more.

There are a few lesser-known types of rayons as well. All rayons differ from one another as a result of the various chemical processes, yielding properties which are all unique from each other.

The reason why all of these chemical processes result in an end product that is not cotton, is due to its distinct physical structure from cotton. Although cellulose is still present, their characteristics have changed. Natural cellulose has a unique structure and set of properties, whereas rayons are synthetic fibers that have experienced some physical changes during their unique chemical processes. To put it simply, a chemical process can never completely duplicate a plant's natural processes.

Towards a Circular Economy

To keep cotton within the closed-loop system, it is crucial to maintain the quality and value of the fiber, which might not be achieved through mechanical recycling as the quality suffers in the long run, and conventional manufacturing tends to incorporate synthetic fabric with recycled cotton to lower costs.

However there is a way for cotton to remain within the closed-loop system, without the exploitative nature of virgin cotton farming. Wood pulp can be harvested from certified sustainable sources, and be spun into rayon. The rayon can be used as is, or incorporated with old cotton textiles to form a new type of fabric.

Such a process is also regarded as upcycling, where old garments, by-products or waste materials are transformed into usable items again. Our team of dedicated researchers are able to achieve this by shredding old textiles and remade them into whole new pieces of clothing, all without sacrificing quality and comfort.

To be able to maintain the value of the resources while reconstructing them into new, wearable clothes at a low footprint, is the very spirit of a closed-loop economy.